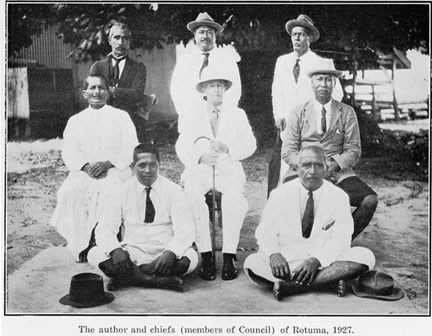

| This account was published in the Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. 51, No. 4 (1942), pp. 229-255. W.E. Russell was Acting Resident Commissioner on Rotuma during 1926-27. ROTUMA By W. E. RUSSELL, Tales and Notes supplied by Mr. F. Gibson,of Rotuma. 1. DESCRIPTIVE. THE island of Rotuma, with its small surrounding islets, lies in latitude 12° 27' 18" S and longitude 177° 7' 34" E. A dependency of Fiji, it is about three hundred miles north by 3° west of that colony, and about five hundred miles westward of Samoa. The main island is divided into two areas by a narrow isthmus opposite the roadstead at Motusa. The eastern and larger area is, from west to east, about six miles in length, with an average width of two and three-quarter miles, the interior "backbone" range rising to about nine hundred feet, densely wooded to its summits. The more irregularly-contoured western peninsula is also wooded and hilly, with diameters, either way, of about a mile and a half. In 1927 the island supported a population of 2243 natives. This has varied little, numerically, since its cession in 1880. Along the eighteen-mile road encircling the main island there is a pleasant motor-drive for the tourist. Starting from Motusa, chief European trading station and the village where visitors land, and striking eastward along the southern side of the island we pass villages here and there, below or above the road lying the remains of "the Great Wall of Rotuma," so styled in a regulation for its communal maintenance. It is a stone fence, originally encircling this main island for the purpose of keeping the numerous domestic pigs to the beaches and away from food plantations, but now robbed and broken for the upkeep of village pig-fences. Between the road and the long white beaches of coral-sand lie, the white-walled houses of many villages, their iron roofs serving as catchments for rain, led into concrete tanks, ensuring a supply of pure water for the villagers. There are no running streams, in spite of the wooded mountains; water finds its way, underground to the sea, emerging here and there, below high-water mark. Brackish wells exist, but from time immemorial the native drink has been the liquid from green coconuts, of which incredible quantities are consumed daily. Tanks, public or private, are closed with mosquito-proof netting. This is enforced by local regulation, mosquitos being the carrier of the filarial germ of Rotuma's curse—elephantiasis. Driving slowly along the unmetalled road little of the tropical scenery is missed. Women may be seen weeding with long-bladed knives to keep their village clean. Their menfolk are away at their daily tasks of food-planting or copra-gathering. Turning north and by west along the return stretch of alternately beaten sand and rougher rockiness, the Government station is passed, with its neat residency -hospital, staff quarters, courthouse, and other buildings, and on to the starting point at Motusa after the eighteen miles circuit. Descending the hill towards the landing place more villages and cultivated areas are seen on the peninsula beyond. To the north lies the high island of Vea, and the more striking islet of Hoflua, cleft from apex to water, leaving a deep passage through which boats and launches may pass between sheer rock walls about two hundred feet in height. At evening the noises of wooden drums or beaten kerosene tins resound. Squeals and rushing feet reply, as droves of pigs race, each to the spot where their respective masters stand with loads of coconut flesh for the evening meal. There is no error or confusion here, for each pig knows his master's voice—or drum. 2. SKETCH OF HISTORY. The Polynesian myth of creation does not directly enter into Rotuman mythology, though the name of the creator, Tangaloa, is known and vaguely venerated. The chief homes of these myths are Samoa, Tahiti, and (in one alternative version, probably introduced) Hawaii, whose traditions, in other, versions, claim population from Tahiti. Many islands of Polynesia attribute their population to migrations from other groups; the creation of lands being due to Mauitikitiki, who—a descendant of Tangaloa—fished them up from the sea. The Rotuma tale of creation has obviously been handed down by the Samoan invaders who claim to have “planted” and grown the island from baskets of Samoan earth poured into the ocean. Mr. F. Gibson, of Rotuma, has furnished me with several Rotuman legends and stories of the past with valuable commentaries. Partly of Rotuman blood, he has had opportunities of research not so readily available to European visitors. Mr. Churchward, however, has secured and published in Oceania (Sydney) a number of legends including some of those recorded by Mr. Gibson. The history of the aboriginal Rotuman appears to be lost to us so far as the pre-Samoan era is concerned. Indeed, apart from the evidence of language, the only trace of these is supplied by the story of the invaders. In a subsequent section on Rotuman legends and traditions I am giving the text of the two versions supplied by Mr. Gibson. Here I shall' merely summarize them as based on historic facts. Raho was the son of the high chief of Savai'i in Samoa—Savaiki in Rotuman. Savai'i, one of the two main islands of the present western Samoa, was at one time occupied by invaders from Tonga, the period being estimated by Samoan genealogies as about 1250-1300 A.D. The invaders were finally driven away after some generations of occupation. Raho's father being styled Tui Tonga (Tongan king) it is possible that this may help to indicate a date for his invasion of Rotuma and support a theory that he was of mixed Samoan and Tongan blood. Raho had a grandson named Lama, and by another wife and her progeny a grand-daughter named Maiva or Maiav, both Rotuman versions of the same name. He had also two other grand-daughters, the twins Nutchukau and Nutchumanga, called the henlepi-herua or sacred female twins of Lepi. The details are given more fully later. The grandson. Lama, quarrelled with his step-sister, Maiva, calling her a foreigner and daughter of an inferior wife. The shamed Maiva begged her grandfather to take her away and find her a new home. With the reluctant consent of the Tui Tonga, ruler of Savai'i, a canoe was built and, steered by one Turifini, put to sea with Raho, his three grand-daughters and others. On the advice of the sacred henlepi-herua, whose guidance Raho appears to have sought in every crisis, baskets of soil from Savai'i were taken on board. After some days' sail Raho, fearing to fall into the hands of marauding cannibals, decided to end the voyage. Baskets of Samoan soil were poured into the sea and the explorers watched it grow up into an island—the island of Rotuma. Having landed his party, Raho departed for Savai'i. Although the names "Savai'i," "Savaiki," etc., are versions of the fabled land of origin of the New Zealand Maori and of most of the Polynesian islanders, the locality of Raho's Savai'i seems settled by the fact of his grandson, Lama, having the secondary name of Tui Samoa. Having visited Savai'i Raho returned, no doubt with further recruits for the Rotuman settlement. He found that the goddess Hanitemaus of Rotuma was contesting the Samoan occupation. Now this Hanitemaus, an archaically Rotuman combination devoid of Samoan elements and meaning "woman of woods," or vegetation—i.e., of the lands—evidently represents the pre-Samoan occupants of the island. She placed tabu tokens—branches—along the coast from the west eastward, to show prior possession. The enraged Raho began placing counter-tabus eastward of hers. He threatened to break up the island, and had begun to do so, witness a great cavity still pointed out (a volcanic crater no doubt), but was dissuaded by the twins, his grand-daughters. Through their mediation, it is said, a meeting was arranged and both sides agreed to live together peaceably. In view of strong evidence indicative of the priority of the ancient Rotuman speech, in which the imported Samoan language has merged, and practically disappeared or been subjected to Rotuman grammatic laws, the evidence for prior possession is in favour of Hanitemaus and her people. Here we may begin the history of Rotuma with the invasion of the island by Samoans who, for a time, took a dominating position and who suffered the usual fate of invaders, submergence in the race of the conquered. The ancient myths of the aboriginal Rotuman race are lost, with the exception of the belief in the Oroi regions where dwell the stealers of souls, of whom more hereafter. Polynesian myths have supervened. The Tangaloan myth, foreign to Rotuma, has a place, though a vague one, The story of Maui-tikitiki, his fishing up of islands and his acquisition of fire, came probably from Tongan invaders. Raho himself was a mere man, not a god or a hero. He came after the mythic era. The so-called goddess of the woods, Hanitemaus, may be taken as the chieftess of old Rotuma, where females still succeed to headship. Of Rotuman history between the Samoan invasion and the coming of the European in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries there may be traces discoverable in clan tradition when further investigated. Some have been published from time to time in a little monthly typewritten magazine issued by Father Sabrion of the Motusa Catholic mission. It may be deduced from some of the place-names, e.g., the state of itumutu (chopped off state) that revolutions occurred, and from martial codes and titles that there were internal wars. The term itu, which may be translated as a state or kingdom, is one of the Samoan words adopted by the Rotumans, and may indicate the introduction of a Samoan political system, though in its administration the ancient Rotuman terms and titles prevailed over those introduced. Thus the widespread Polynesian key-word ariki (Samoan ali'i), a chief, has vanished, replaced by the vernacular gangatch of archaic Rotuman. It appears that at some stage of history a mua and a sau held sway over the states of Rotuma. That this was after the arrival of the Samoans is shown by the Polynesian—and indeed also Fijian—-words mua and sau, respectively "leader” and "high chief." The tale is mixed myth and tradition, the gods, and the man Raho, with other mortals, being the characters involved. The following is a resume of Mr. F. Gibson's translation of the Mua and the Sau tradition. It is given in full later. The Mua and the Sau lived in the heavens. The name of the Mua was Tuipena. He had a daughter, called Parengaoau. The Sau's name or title was Tui-te-Rotuma. He had a son named Fangatari-roa. Looking down on the earth these gods saw an island. They sent an envoy to explore it and to report to them. The envoy found it such a pleasant land that he remained there. From the Sau's "Tuiterotuma" title, presumably the island was already known as Rotuma. As the envoy had failed to return the Sau's son and the Mua's daughter, with two attendants, were sent down to Rotuma. There the daughter became pregnant to Fangatariroa, the Sau's son. The shocked attendants hastened to report this to the gods, but were told that it was just what was intended. At this time Raho, the Samoan invader, seems, by the story, to have ruled Rotuma or a part of it. Two children were born to Parengasau. The parents failed to follow the correct procedure of reporting the births to Raho. On the birth of a third son, however, they notified him, with the request that he should name him. Ignoring, on account of the breach of etiquette in the failure to report their births, the elder sons, Raho named the third son Tui-te-Rotuma and appointed him Sau, or ruler, of Rotiima. Since then there has always been a sax, titular ruler of all Rotuma. The title later became a merely ceremonial one, by election for six moons. Through, probably, territorial disputes, Rotuma ranged itself into six states (itu). A seventh was subsequently detached from Itu-tiu (great state) and named Itu-mutu.

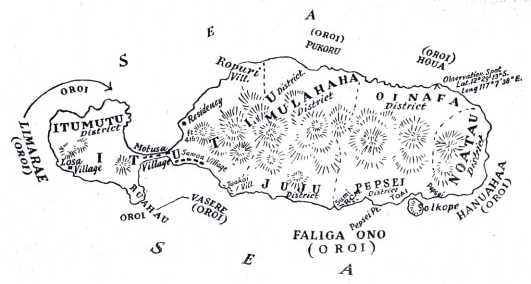

Rotuma Outline and features from Natutical Chart of 1896. Scale [in original, not in electronic version], 1 inch = a little over five-sixths of a sea-mile. Note.—The names marked Oroi are spirit-abodes under the sea (see Section 5, 'Oroi').

ROTUMAN LEGEND AND TRADITION. There is the story of a raid on Losa by cannibals who had hidden on an outlying islet. From the young men's sleeping-house men on several nights had disappeared, their mats being found covered with blood. Losa, lying near to a submarine region known as Oroi, whose inhabitants, malignant spirits of the dead, emerged by night—as elsewhere described—to steal the souls and devour the bodies of men, the disappearances were at first attributed to these. But, from a hill top, a villager espied the lurking canoes of strangers. The truth was then realised and armed guards were placed within the sleeping quarters. Late at night footsteps were heard and two men crawled through the low door, to be promptly clubbed by the guards, and thrown outside. Thinking the bodies to be those of further victims the marauders were dragging them away when they discovered them to be their own people. They fled, pursued by villagers, and gained their canoes, but in their haste ran on a rock—ever since called "the rock of help"—were caught and killed. The survival of the name, in archaic Rotuman, given to the rock, denotes the antiquity of the story. A few hundred years ago there was a Tongan invasion. From the fact of the remains of their tombs in various places being still pointed out, and from current tradition, it is clear that they obtained considerable power. They were all, it appears, massacred in a single night in a revolution organized by one Ali'i, evidently, by his name, of Samoan descent. MODERN HISTORY. The history of Rotuma after its discovery by Europeans is of little ethnic interest, though the accounts by early voyagers of the conditions of life in the island in those days, already given, throw light on the past. Shortly, modern history runs as follows: 1791. Discovery by Captain Edwards in H.M.S. Pandora. 1797. Arrival of the missionary ship Duff. From this time onward various ships, the Rochester, the Maquary and others visited Rotuma. Deserters from these remained, and escaped convicts from New South Wales began to join them. In 1835 there were about eighty whites on the island, most of whom died violent deaths in quarrels or native war. 1824. The French ship La Coquille arrived with M. Duperry. He estimated the population at 4,000: the natives were, he said, stained yellow with turmeric. In 1827 came Captain Dillon, commanding the Research. He found that some one hundred families had recently emigrated to Samoa. In 1928 arrived Mons. Legoaraut in the Tromelin. He described them as copper coloured, and wearing moustaches. They were naked, except for a genital-covering or sling and a short loinmat. They dressed their hair with a topknot. They wore ivory ornaments, and greatly prized whale teeth from which these were made. They were tattooed from body to knee, leaving only the genitals clear, with designs of flying fish and flowers. War was waged with fifteen-foot spears and with clubs and stones. The chiefs fought personally. Circumcision of youths was practised. Women were respected and eligible for clan chieftainship. At death the body was exposed on a mat with a wooden support for the head. The body was first painted (stained probably) and then carried to the grave on mats. The widow, if any, cut off her hair and burned patches of her body. When a chief died two boys were killed and buried with him. If a chieftess died two girls were similarly killed and buried. Graves were lined with stones. There was no belief in a life after death, but there was a supreme god who killed by suffocation. The dead were called "atoua." They respected rats and would not kill them. At a betrothal the pair were put to sleep together for the night, but were watched so that nothing might occur. At marriage, after feasts, dances and the presentation of mats, the couple were escorted to the sea where each, lying supine, was washed by the other. This concluded the ceremony except for its comsummation, which took place under the supervision of an old woman. If the tokens of virginity were absent the bride could be sent away and would be considered public property. Before marriage, however, girls might grant their favours at will (which leads one to think that the rule of divorce for previous unchastity could not have been generally enforced). After marriage fidelity was expected on both sides. For a breach of this a man might club his wife, or the man might be set adrift in a leaking canoe far out at sea, with hands and feet tied. (This custom, again, could only have been an occasional act of clan vengeance.) The foregoing gives most of the early visitors' notes on the customs prevailing in their times. Some of these are borne out by the survival, to-day, of traces of these customs, modified by civilisation. The disbelief in a future state is negatived by the practice of providing a deceased chief 'with buried attendants. A fair amount of European blood must have been infused into the Rotuman race after this. M. Duperry's guess of a population of 4000 was an over estimate. The population since 1880 has remained fairly stable at about 2,200, and there are no stories of epidemics or great slaughters to account for a decrease. The seventy whites with large half-caste families alleged by Charles Chowe Howard to have been in Rotuma on his arrival, perhaps about 1836, would have made an impression quite perceptible in a century. The village of Hanga is mainly peopled by Howard's own descendants. As a matter of fact, the Rotuman, as a race, is paler than the average Samoan or other Pacific islanders. They, indeed, call themselves "white" and style other islanders "black men." In 1842 Samoan Methodist catechists, but no European mission-aries, established themselves in Rotuma. In 1837 Mons. Montpellier had attempted to land French missionaries, but had failed. The introduction of Methodism, therefore, dates from 1842, though European missions were not established till 1864 when the Methodists, and (in 1868) the French Catholics, gained permanent footings. There appears to have been war in 1851, said to have been due to rivalry between the Malahaha and Oinafa states. Between 1871 and 1878 frequent wars between native adherents of Methodism and Catholicism were waged. A sanguinary battle was fought on 28 February, 1871, the Methodists being conquerors. In 1872, a French warship visited Rotuma. In reprisal for the damage to the Catholic converts the commander levied a heavy fine in copra to be paid by the Methodist states. He sailed away and war was renewed. By this time there was an increasing influx of European traders who were allowed to open stores and stations, subject to an annual payment, or credit, to the ruling chiefs of the states in which they lived. After cession these amounts were used as a basis on which to determine the amount of taxation to be contributed by each state or district. The French intervention was the deciding factor which drove the chiefs

of Rotuma to offer cession of the island, through the Governor of Fiji,

to Great Britain. The island was weary of war. Waged now with guns and

rifles the sanctity of age or rank had no protection. The young men

were drifting abroad on trading ships to Australia or elsewhere finding

ready employment, especially as pearl divers.* They returned, if at

all, with diminished respect for their chiefs and elders. The power

of the chiefs was waning Religious war continued, more or less fiercely,

up to 1878, when, the chiefs of the island, encouraged by settlers and

the Methodist mission, and with the consent, I understand, of the majority

of the Catholics, met and decided on cession and protection.

The offer was sent to Fiji by the hand of Marofu, ruler of Noatau,

the premier state. This offer was despatched duly to England and approved.

Terms were arranged by emissaries from Sir Arthur Gordon, then Governor

of Fiji. A constitution was granted under which the island was to be governed by a resident commissioner responsible to the Government of Fiji, with the assistance of a council of chiefs empowered to pass local regulations. The general laws of Fiji, where applicable, came into operation. This continued till 1927 when improved facilities of communication made it possible to co-ordinate administration more closely with the Fiji Government. The seven states of Rotuma became districts under the new administration of 1880, each with a high chief-the pure ngangatch-in charge. Under successive resident commissioners the Rotumans have led a peaceful and happy existence as British subjects ever since annexa-tion. 3.LANDS AND TENURES. On assuming control of the dependency of Rotuma, after its cession to Great Britain, the Legislative Council of Fiji framed a constitution and form of government which was duly approved and authorised through the Secretary of State. This was partially tentative—"till further order be taken." The first Resident Commissioner was Mr. Hugh Romilly who held the first Council of Chiefs, authorised to make regulations under the constitution for its better carrying out in detail, and, generally, for the good government and welfare of the natives. This was in the year 1880. In 1882, Mr. Commissioner Mitchell held inquiries into the ancient and existent customs and rules of land tenure and succession. These were ascertained by declaration and agreement of assembled chiefs, and regulations, as far as possible, in conformity with the information gained, were adopted. It was not, however, until 1917 that these were fully con-solidated by Fijian ordinance. Mr. Mitchell was hampered in his preliminary enquiry by want of Polynesian experience, his previous experience having been in Fiji where the political systems of the natives had developed on tribal lines, their leaders sacred on account of direct lineal descent from the deified patriarchs, founders of their tribes. The application of English terms to Rotuman social phases is difficult, and unskilled or illiterate interpretation—there was no other available at the time— would confuse and perplex the chiefs under examination as to their customs. Probably owing to this the facts of group, and not personal, land ownership, differing in many respects from Fijian tribal tenure, seemed to have to some extent eluded Mr. Mitchell. These were, however, elicited by later commissioners, and embodied in land ordinances. Rotuma was, from time immemorial, divided into seven independent itu, or states, now districts, and a pure ngangatch, or king, ruled the clans composing the population of each. With the interior economy of the clan in relation to its lands this ruler did not interfere, each, as later explained, having its own chief or pure. As related in my history section a band of Samoans at some period in a distant past invaded Rotuma and found it occupied, but were allowed to remain and settle. It is probably due to these settlers, and their following train of Samoan immigrants, that the itu, or states, were introduced, the words itu and pure (ruler) being both of Samoan origin. Much of the land and succession custom is also Samoan. Division into family clans, each claiming the land around its food cultivations, caused withdrawal into villages for mutual aid and protection, and aggregations of related villages became states. All this was in accordance, as I have said, with Samoan policy. It may be assumed that, amongst the invading Samoans, women were much in the minority. It follows that the subsequent generation had, mainly, Rotuman mothers. As time went on the Samoan strain would weaken, as would, also, the traces of the Samoan language. Not so the rules of land tenure, introduced to a cruder civilization—if any—by a more developed one. These have remained. Each state contained an independent federation of family groups (kauanga) occupying lands and villages, the former under a pure who succeeded to his office according to rules given later, the latter under a pure whose powers were mayoral only. The next social division is the hoisasingi (or clan). The strict definition of this word was given by the chiefs and elders in 1882 as "brothers and sisters" (this including cousins of the same generation) "and their children for three generations." Here the hoisasingi—translated, "band of brethren"—ends. The next generation are koinanga of the clan (distant relatives) and may live with or away from it. Fiji Ordinance No. 1, 1917, confirms the customs of tenure. "The land is held by family communities" (i.e., hoisasingi) "in undivided ownership. The head and overlord of the community is its pure. Individual members of the community have life interests, only." The succession to pure-ship of the clan and its land devolves by seniority. The clan consists of (a) the senior generation, of which the senior member is pure. Three generations of their progeny—, b, c and d-complete the membership and are kauanga to each other. The succeeding generation is koinanga to the clan, as explained above. The rules of customary succession following must be construed subject to the fact that the words "father" and "uncle" are synonymous as are, also, "mother" and "aunt" and "brother," "sister" and "cousin." The definition of hoisasingi (to which the nearest English equivalent is "clan") limits membership to four generations-a, b, c and d. A. On the death of the chief (pure) for the time being he is succeeded, normally, by his brother next in age. If no brother, the senior cousin, male, succeeds, to be followed, in case of death, by brothers or cousins in order of seniority. As I have indicated there is no word distinguishing cousin from brother. Should occasion arise a description of the degree of affinity would be necessary. On failure of males of the A generation females succeed in similar order. B. On exhaustion of generation A the next generation steps in, in the person of the son, if any, of the first pure of the preceding one, and generations C and D, on failure of generation B, follow, if available, in the same order. It is plain, however, that generation A may last many years and, with the second generation intervening, a lifetime may pass before generation C has a chance. Before this stage exogamy, with the prohibition of cousin (or, to the Rotuman mind, brother and sister) marriages has alienated the progeny of at least generations C and D, and merged them in other clans. As regards clan rights and privileges I have already shown how the apparent exclusion of a fifth generation does not, in practice, come into operation. It was, as a matter of fact, only considered at the enquiry in response to Mr. Mitchell's questionings, and the resulting declaration by the chiefs was just a courteous reply. It was, however, at another stage of the enquiry, stated that in war-times the parent state might call for the service of the koinanga or relatives. The rule of the clan pure over clan and land, though absolute and dictatorial, even to the right of denial, for sufficient reason, the fruits of his toil to a cultivator, was qualified by mitigating principles. The chiefs declared that pures were bound by certain rules. Each member of the clan is entitled to a fair share of the land's produce, as well as to house and garden lands, "so long as he is obedient to his seniors." He cannot exercise his rights without the pure's consent. If, however, the pure refuses rights to a member of his own generation without just cause the elders might hear, with, I understand, the head of the state, a claim for a separate allotment of land for life. Amongst other declarations of custom connected with land is one stating that only the senior generation can claim to exercise interests. Their sons can only request concessions through their parents or uncles, the grandchildren through the two intervening generations. But in practice, so far as I could discover, no reasonable request is refused, and the records since annexation show no appeals to the resident commissioners against denial of privileges. Another declaration discloses the fact that the word "illegitimacy" conveys nothing to the Rotuman mind. All children are to them legitimate. The customary rules of succession to clan pure-ship appear to have been, at times, abrocated by a dying pure nominating a successor. The foregoing account is based on the records of Mr. Mitchell's enquiry into land customs, on the agreed declarations of the assembled chiefs, on my own enquiries and experiences when arbitrating on land questions, and on the Rotuman Land Ordinances.

4. MYTHS AND TRADITIONS. Foreword. The Rev. C. M. Churchward has published in Oceania (Sydney) a series of Rotuman legends, some of which are versions of tales given me by Mr. Gibson. I have here omitted some of the latter, confining myself to those either differing materially in version from Mr. Churchward's, or carrying clues to the ancient history, ways, and superstitions of the people. With these I have embodied the substance of some notes and explanations by Mr. Gibson on the legend of the Mua and the Sau. In the matter of personal and place-names I have thought it best to give these in accordance with English phonetics, Mr. Gibson having used the letter-values adopted to simplify, for the native, the arts of reading and writing. In the cases of his G and J, which in Rotuman are sounded as ng and tch (the latter by the Catholic missions as ts) I have given these the English spelling. The vowels are as in Italian, and a terminal vowel is always sounded, except in a diphthong.

Charles Chowe Howard, of Rotuma

THE "PLANTING" OR ORIGIN OF SAMOA. First Version.* [* In my history section, ante, I have summarized the historical result of this and the second version.] Raho, a chief of Savaiki (Savai'i, Samoa) had a grandson and a grand-daughter, the latter named Maiva. As the grandchildren one day were collecting shellfish they quarrelled, the grandson, who was lame, accusing Maiva of stealing his catch of shellfish. Maiva, much insulted, begged her grandfather to find her a home away from Savaiki. They put off, accordingly, in a canoe, taking with them a basket of soil or sand. After many days sail Raho threw the soil overboard, and from this the island of Rotuma grew up. After landing his grand-daughter on the island Raho returned to Savaiki. In his absence a goddess called Hanitemaus appeared. She was the goddess of trees and vegetation. On the island at this time were twin goddesses of the coast named, together, the Henlepiherua. The goddess, Hanitemaus, claimed possession of all the land, and notified her claim by tabus, planting branches along the coast, beginning from the western end. Raho then returned from Savaiki. He was very angry and began planting tabu-branches from the eastern end. The rival claimants finally met and discussed the matter. Hanitemaus claimed priority, pointing out that the leaves on Raho's tabu were still green while her branches were dry and withered. In his wrath Raho threatened to break up and scatter the island. Taking his digging stick be began by striking the earth, causing the great hole called Mamfiri at the western end of the island. The twin Henlepiherua, however, persuaded him to desist. The conference ended in an agreement for all to live peaceably together. Raho then sailed off to Savaiki, returning with many followers who settled in Rotuma. His and their descendants became chiefs and leaders of the people. THE PLANTING OF ROTUMA. Second Version. One Tuitoga and his wife Sinafakatofua lived at Savaiki (Savai'i in Samoa). Their two children were named Raho and Mamafiarere. Raho married a woman called Mafiaatu. They had two female children, the elder called Mamaere, the younger Vaimarasi. The parents were especially fond of Mamaere. The house assigned to her had two doors, one facing east and one west so that she could see the rising and the setting of the sun. Mamaere became pregnant. She bore twin girls Nutchukau and Nutchumangi. These were much honoured by the people, and received many gifts. Later Vaimarasi, Raho's younger daughter, was taken to live in the compound of the king of the land whose chief wife was Moriakevia. Vaimarasi and Moriakevia became pregnant at the same time. When it became known that both were with child the whole of Samoa prepared for a celebration, and mats and tapa (bark-cloth) were made by the women. Now Raho was very anxious that Vaimarasi's child should be the firstborn. He went along to his twin grand-children, Nutchukau and Nutchumangi, and asked their aid. They said, "Alas! It is a shame that the chicken should spoil the hen." Raho replied that this mattered not. In due time Vaimarasi was the first to give birth, and to twins, male and female. The male child was not physically whole. He was called Moeatikitiki. The female child was named Maiva. There was great feasting and rejoicing. Moriakevia—the chief wife—then gave birth to a male child, who had a deformed foot. He was named Tui-samoa. Maiva and Tuisamoa grew up together. One day Maiva called all the young girls together and went to the sea to fish. Having caught a red fish, the penu, she put it into a coconut shell, and returned to the sea. Her brother, Tuisamoa, whose other name was Sumera, came along the beach, saw the fish, and hid it in his mouth. When Maiva missed the penu she accused Tuisamoa, but he denied the theft. She pointed out the prints of his deformed foot on the sand and, leaping on him, tore the fish from his mouth. Very angry Tuisamoa called her a foreigner without claims on the family, while his mother lived in the Suura or chief wife's house. Maiva was shamed and complained bitterly to Raho, begging that he would take her away to some other land. Raho also was upset. He consulted the twin grand-daughters, Nutchukau and Nutchumangi, known as the Henlepiherüa, or twins of Lepi, and they decided on a plan to lighten the sadness of Maiva. The twins instructed Raho to go inland, fell a suitable tree, hollow out a canoe, and tell them when it was completed. When the canoe was made and brought to the coast the king heard of it and spoke to Raho, asking him not to go away, and saying that he would find some near land where Maiva could live. To this Raho would have agreed, but Maiva could not forget her wrongs and wished to go far away. In the meantime the sacred Henlepiherua had prepared baskets filled with earth. The whole party sailed away leaving Tuitonga (the great-grandfather) and Vaimarasi her mother, who wept and was inconsolable. The canoe was steered by one Tarifini and contained Raho, Maiva, Nutchukau and Nutchumanga, besides others whose names are forgotten. They were many days at sea. At last the twins thought it was time to plant an island. Raho agreed to this, saying that they had sailed far enough to westward where lived ferocious people who might be travelling around and would seize and eat them. From their baskets they then spilt overboard some of the earth they had brought. This earth formed the Vaimoana reef near Rotuma. After casting about they found on this a rock which they called Hofkamea.* [* Hofkamea is opposite the Malahaha district of Rotuma.] Then Raho proposed that they should move further on. They did so and the twins then emptied the rest of the earth in their two baskets on to the rock. In a short time the island of Rotuma grew from this. Notes by the compiler. In the second version of the foregoing legend many traces of Tongan influence are seen. Raho's father, with the name of Tuitonga, may, though not necessarily, have been of Tongan origin, while his mother, Sinafakatofua, which name I take to be translatable as "mother from Tofua" (an island in Tonga), seems also to have been Tongan. The name Moeatikitiki, given to Mamaere's son, also suggests Tonga, where Mauitikitiki the equivalent of Moeatikitiki, was the fisher-up of that and many other groups and islands. Raho's era, even, may, conceivably be, approximated by the fact of the occupation of Savai'i (Savaiki in Rotuman) in Samoa by Tongans in, according to genealogical data, the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries, and their final expulsion by the Samoans under Malietoa. Raho may, with his followers, have been of mixed Tongan and Samoan blood. THE LEGEND OF THE MUA AND THE SAU OF ROTUMA. The Mua and the Sau looking down from the skies saw this land and sent one Titofona down to investigate. Of course if there were cannibals there Titofona might be eaten, but, if not, he was to report whether it was a goodly land and whether inhabited. Finding it a pleasant land Titofona stayed there with a man called Toval at Fonofono. Now the Mua had a daughter called Parengasau. His own name was Tuipena. The Sau, whose name was Tuiterotuma, had a son named Fagatariroa. As the messenger, Titefona, had not returned, the Mua and the Sau sent their, two children down to this land accompanised by two men Moeanita and Orevai. After staying for some time Parengasau became pregnant by Fangatariroa. At this their guardians, Moeanita and Orevai, were very angry. They reported matters to the Mua and the Sau. They were told to go down again as what had occurred was in accordance with the parent's intention. Their first child was called Muasiotanganono and the second Semarefainga, but when the third child was born they thought they had better notify Raho before naming him. Raho said, "Very well, seeing that this is the third child and the only one the parents have seen fit to tell me of he shall be called Tuiterotuma, and he shall be the first ruler (sau) of the land." Raho further told Moeanita and Orevai to tell Parengasau and Fangatariroa to have a mare (green) cleared at Halafa, to be called Muaariki and that they were to go to the sky and bring him whole food from an oven there. The Mua and the Sau had the food prepared, and Orevai and Moeanita brought it down from the sky. Here one Semarefainga asked them where they were taking the food to. They replied that they were taking it to the Sau. Semarefainga took the food and made an oven, taking for himself part of the pig and giving them the other part for Raho. On their arrival Raho was very angry because the pig was not whole. He took the piece sent to him and threw it into the sea where it turned into a rock called "the boar" at Hatana. After the two men had returned from the sky the young Tuite-rotuma died and his parents told them to go and inform Raho. On their doing so Raho said that he would not go himself, but that they were to return and make a stretcher on which to lay the Sau and take him to the middle of the island. Raho would send two birds, Monteifi and Monteafa, and these birds would precede the funeral. At a certain spot the birds would seem as though about to alight. At this spot they would find all preparations made for a native oven (koua), and taro growing nearby. This would be Tuiterotuma's burial ground, and it would be the cause of an abundance of food for the future. Not long afterwards Fangitariroa died. He was buried at Fangroa. This makes the second burying place of the family. After this one Vilo arrived from Samoa in his canoes. On leaving he left behind him a man called Tuanofo who, later on, married Parengasau. Their first child was called Takalholiaki, the second Tukumasui, and the third Muameata. Later on the state of Noatau made war with the object of capturing Tukumasui (who must then have been Sau) to keep him in that state. In this they failed, though they took away his brother, Muameata. The chiefs of Noatau then installed one Riamkau as a rival Sau. The following is from Mr. Gibson's notes on the above legend, but seems to refer to a more modern phase than that of the period when the saus were descendants of the divine Mua and Sau, and held office for life as supreme rulers of the whole island:— "The term or reign of a Sau, was six months, known as a tafi. Rival saus were quite common. In the choice of a sau much depended on the ability of his tribe or state to support his position, which they must do, even though distant from his prescribed state of residence, with food and goods. He could have many wives, but one, only, was the chief or legal wife. Should a clan or state not have an eligible successor to its chief they could send one of their women to the sau's compound in the hope of suitable progeny. The chief wife was styled fainohonga, the others norua. The last sau was Suakmaasa, living at Feavai. After losing the battle of Ngasava, February, 1871, he resigned. His son is still called Tui-Rotuma, ceremonially." THE LEGEND OF MOEATIKITIKI. Tangaroa, the supreme god or aitu, who lived in the sky, had a son named Lu whose wife's name was Mall. Their eldest son was called Moea-langoni and the second son Moea-motua. The third birth was an abortion. Lu, taking the aborted foetus, threw it into the scrub. Tangaroa, seeing this from above, sent heavy rain which washed and

revived the abortion so that it came to life. There came by a ve‘a*

(land-rail) who took the baby to its nest and nurtured it. It grew into

a strong and healthy boy. She told him of his parents and their abode. One day Moea-tikitiki* roaming near his parents' home, saw his mother

approaching and ran away. He told this experience to the ve‘a,

his foster-mother. She told him to go there again next day and to again

run away if seem, but to repeat his visit on the third day, stay, and

make himself known. Moea-tikitiki acted as instructed. On the third day he made himself known. The parents were overjoyed, an oven was prepared and there was feasting and gladness. Moea-tikitiki remained with his parents and his brothers—Moea-langoni and Moea-motua. Lu, the father of the three Moea brothers, had his plantation at Tonga, under the sea. He went there daily, but would not allow any of his family to accompany him. As Moeatikitiki grew older he became curious about his father's journeyings. One night he resolved to follow him in the morning. When his father was asleep he tied a corner of his loincloth to his father's genital-cloth and in the early morning, when Lu moved he was awakened. He feigned sleep while his father looked into his face. Lu untied the knot and went away suspecting nothing but a boy's joke. Moeatikitiki followed his father. He saw him remove a stone, descend, and replace it from the underside. The boy waited a while. Then he went underground in the same way, and saw the land of Tonga spread below him as far as he could see. Reaching up to him was a malay apple tree (hahia) by which his father had gone down. Moeatikitiki climbed down, but before reaching the ground plucked a ripe fruit from the tree, pecked it as a bird would, and threw it at his father who was weeding under him. The fruit struck Lu with such force that he became unconscious. When he came to he picked up the fruit and seeing it, as he thought, pecked by birds he went on with his weeding. The boy then plucked a second fruit, pecked it as a ve'a (landrail) would and threw it at his father who again fainted. After the father had recovered from this the boy took a third fruit and, after taking an ordinary bite out of it threw it, also, at Lu who became unconscious once more. On his recovery Lu saw that it had been bitten by a human being and, looking up, saw Moeatikitiki in the tree. Calling him down Lu scolded him for always being up to mischief. He then sent him away to cut a bunch of bananas of a kind called parimea, at a certain spot. There two large birds (kaloe) flying round and round the bunch resisted him. Moeatikitiki, having killed the birds, took them, with the bunch of bananas, to his father. The latter again sent him away to bring a root of kava. The boy found the kava under the charge of two great bull-ants who gave him much trouble for a while, but these also he killed. On Moeatikitiki's return with the root of kava Lu was more than ever determined that the boy should die. He commanded him to go to an old man who lived some distance away, and to get from him some fire to cook their food. On arrival at the old man's hut the boy was refused fire. After a heated argument it was agreed that they should wrestle for it—the winner to keep the burning log. The old man swung the boy round and round and then threw him up into the air, but he landed on his feet and again grappled the old man. This time it was the old man's turn to be thrown up into the air, and much higher than the boy had gone. The old fellow acknowledged defeat and gave the boy the fire-log. He also said that some day he would again help him, through his foster-mother, the ve'a. On the boy returning to his father with the fire the latter thought it was useless to try and kill the boy that day, so, after they had eaten, they returned home. Soon after this the three brothers went out fishing in their canoes. Moealagoni got the first bite. He asked his brothers to guess what fish he had hooked. Moeatikitiki's guess of a kairi proved correct. He also correctly guessed an ioro (shark) when Moeamotua hooked a fish. Moeatikitiki then hooked something. While his brothers were guessing he heard the ve'a calling out from the shore. This reminded him of the old man's promise of help. He told his brothers that he had not hooked a fish but had struck the land called Toga, which he there-upon pulled up from under the sea. At this Tangaloa, who was watching them from the sky, became very angry.

He took them up to the skies and turned them into tupua.

These tupua are the three stars* that we

see in a row and that are known to us as the three men, Moeatikitiki,

Moeamotua and Moealagoni. THE LEGEND 0F AIATOSO AND HIS SISTER RAKITEFURISIA. Two brothers lived with their wives on the western side of the island of Uea. Both impressed on their wives that they were never, even if very hungry, to cut down a certain bunch of bananas of a kind called sae. As this bunch appeared to be everlasting the elder woman, one day when the brothers were away fishing near Hatana, said to the younger, "Let us cut down this bunch of sae and cook it. They are so secretive about it." The younger woman demurred, but finally the elder had her way. She took a shell-hatchet and cut into the stem of the plant. From the cut came groans, and blood spurted forth. The women realized that they had done something very wrong, but later the elder hardened her heart, put the bananas in a basket and threw the stem over a cliff into the sea. The stem floated away toward the brothers, who were fishing and not intending to return until late in the evening. As it was nearing them they heard a cry of "ku!" but on looking up and seeing nothing they thought it was imagination and went on with their fishing. The husband of the elder woman was the one nearer the banana-stem which was now quite close to them. It was fast getting dark. Then, for the second time they heard the "ku!", and then, seeing the floating object, knew that the call tame from it. They looked at one another and began pulling up their lines, after which they paddled with all their might toward Uea. A little time later the husband of the younger heard, from his canoe, a great splashing and an agonized yell from not far off, but as night had closed in he could see nothing. He kept on paddling hard towards Uea, expecting every moment to find his canoe held or a hand laid on his shoulder. When he reached their landing place he was exhausted and trembling with fear. Making an effort he managed to get on to the landing rock, leaving his canoe afloat. His wife, who, feeling guilty of wrong doing, had come to meet him, managed to save their canoe. When the husband was able to speak he asked his wife what they had

both been doing while he and his brother were away. She then told him

all, explaining that she had been against touching the bananas. Her

husband then told her that the tree was his mother turned tupua*

and that they must go away at once to the other side of the island facing

Rotuma; otherwise they would be killed that night. They got into their

canoe and paddled away. Meantime the wife of the elder brother had entered her house in a defiant mood and gone to bed. At midnight she was awakened by a voice—which she took for her husband's—calling to her, and asking where was the wooden bowl of water. She sleepily replied that she had filled it with fresh water and that it was just inside the door by the wall. The door was then opened and a voice said, "I will now serve you as you served me today." She was then torn asunder by the tupua stepmother, who then went to look for the other man and his wife. These, two had now landed at the other side of the island, and were making for a hut up on the hillside. The man was urging his wife along and helping her, telling her that there was no time to lose. On approaching the hut they felt terrified and as if there were something close behind them. As they drew near the hut a voice called out, saying that there was no hope of escape for them. They redoubled their pace. As they entered and closed the door there came a great thud against the hut and a voice called, "You men have bad wives. I have had to do away with one of you and have just torn one wife to pieces. You and your wife have escaped for a time only.” The pair went in great fear and very cautious, but as time went on they became less fearful. A son was born whom they called Aiatoso, then a daughter whom they named Rakitefurusia. Fear was forgotten and they went on with their daily tasks, mingling with other people as though nothing had happened. The children were growing up and the boy was able to go to the plantations with his father, while the girl helped her mother at home. One day the children were playing outside the door, while the father had gone fishing and the mother was making a mat in the house. Suddenly she felt as though a strange presence was about but, looking up, she saw nothing. Shortly after this she heard a splashing in the bowl of water, followed by a thud inside their bundle of mats at the sleeping end of the house. This was repeated, but she could still see nothing. She then thought that she would listen quietly and watch the bundle of mats. As soon as she again heard a splash she glanced sideways at the bundle, and, to her horror, saw her husband's foot and leg, below the knee, above which it had been cut off, fly into the bundle of mats. She quickly got away from the house and, running to the landing, plunged into the sea and swam toward Lulu, at Rotuma. In her haste she had forgotten the children, but now, being certain that by this time they had been eaten up, she looked back, weeping, and then swam on. That place is called Ounga (lamentation) to this day. A tupua, called Taumatef, turning himself into a man, approached the children at Uea. He told them all that had happened. He then instructed them to enter the house and that as soon as they saw the knee fly into the mats they were to jump on top of the bundle and say to their father that they were sorry for his being wet all day at fishing and would lift and swing him to sleep. Then, while doing so, they were to gradually take the bundle to the shore and throw it into the sea. He said that this was the only way to save themselves. The children entered the hut and did exactly as directed by the tupua. As they drew near the sea they gradually increased the motion and at the edge they gave an extra heave and let go. This spot is known today as Atinga. The tupua, Taumatef, then told the children that their mother had reached Lulu beach, but that, to save herself from being eaten up by the ten-headed tupua there, and thinking that they were already eaten to the knees, she had—as she thought—lied to him by telling him that there were two children at Uea, and begging him to spare her. This he had agreed to, but he was coming over that night for them. The children were very frightened on hearing this and begged Taumatef to save them. He said that they would be saved if they got a conch-shell to blow and other shells to rattle, with anything else they could think of to make a great noise to frighten him as he landed. If he asked them what they were doing they were to say that they were making a net for the devil of Lulu. On hearing the great noise, and their answer, he would be frightened and would go away, but would return and try to get them ten times—a try for each of his ten heads. For the tenth try there must be different tactics. On the tenth day, when the tenth attempt would be made, he would be so hungry that he would first gorge himself with ivi-nuts under an ivi-tree near the landing. They were to prepare for this by gathering ivi-nuts and making a heap under a big over-head branch. They were to cut through the branch till it would be just ready to fall by the tenth day when, instead of being in the house, they were to await him in the tree, ready to cut the branch as he made for them. The children thanked Taumatef, and he went away. For ten days the children followed Taumatef's instructions and events

occurred exactly as directed, the ten-headed devil being killed by the

falling branch. The children lived on happily at Uea and grew up a handsome

man and woman.

Translated-

Rakitefurosia was, at this time, preparing food and at first she did not realize that he was singing from above. When this dawned upon her she became frantic with grief. She ran about, beating her breast and imploring Aiatoso to come down to her. She followed after the basket up the mountain side as it rose till she reached its highest peak, and there, weeping, raised her hands as though to fly after him. Finally she sat, while his chant continued, and then chanted back to him.

They continued chanting till, to the girl, the basket became a speck and she could only faintly hear his voice. Then it disappeared and the voice ceased. Rakitefurusia was so stricken with grief that she could neither move nor eat. She just sat on night and day, thinking of the perils she and her brother had endured together and of the happy days she had spent preparing his food while he was working on his plantation. Aiatoso, on arriving in the sky, was alloted a house, the end door of which he was told never to open. Day after day he refused all food and drink offered him. On the tenth day he opened the end door and on looking down saw his sister sitting on the summit of the hill, motionless. Taking a sprig of the blood-red mairo bush he threw it down. It floated downward through the air and fell beside her, but she did not move. He broke off another and this also dropped beside her, but still she did-not move. He then begged to be let down, and was finally allowed to go. As he alighted on the hill-top he rushed to her and caught her in his arms but found her to be lifeless, so he sat down beside her and died there also. This spot is called "Sarafui," or "the garland that missed." The girl's footprints, made as she was leaping with outstretched arms and calling to him are still discernible under the bushes. THE TWO SHARKS OF FAKPUI. A man and his wife lived at Fakpui. They kept two sharks in a pool leading to the sea. There was also a stranger living with the couple. One day this stranger asked to be sent to his home in a distant land, and it was agreed that the two sharks should take him over the sea. His hosts impressed on the stranger that when he reached his home he was to pour fresh water over the heads of the sharks to get the salt out of their eyes, and before they set out on their return to point their heads in the direction of Rotuma. The stranger promised to do all this. Next day they went to the pool and the man told the sharks to take the stranger to his home. They set out together after the stranger had bid his hosts a tearful goodbye. On arrival at the stranger's home he called out to his people to catch and cook the sharks for eating. They rushed to the beach, but the sharks escaped, reaching Fakpui after a long and trying voyage, severely wounded. They told the couple everything that had happened and the hardships they had undergone. The woman said, "Very well, tomorrow night I will set out with you and we will get that stranger for your food." Accordingly they set out on the following night and in time arrived at the stranger's land. The woman went ashore at night to peep into the houses. At the third house she found the stranger, and heard him, tell the people there that if they had only hurried themselves at least' one of the sharks would have been caught and eaten. The woman then planned to wait until the inmates of the house were asleep when she would go in, lie beside the stranger and gradually work the man nearest him off the mat, repeating this with the man on the other side of him. He would then be alone on the mat and easily wrapped up to be taken away. In this she succeeded and' carried him down to the sharks. They set out on their homeward journey. On their arrival at the Fakpui pool they found the man awaiting them. They carried the stranger, still wrapped in the mat and laid him on the, bed he had formerly occupied. At cockcrow the stranger starter, saying, "Boys, that is like the crowing of the cock at Fakpui." At second cockcrow he again started, with the same remark. By this time the stones in the oven were red hot. The strange was awakened and told of his approaching doom. He cried for mercy but was asked what mercy he had had for the sharks, and was told that instead of him and his people eating them the sharks would eat him. The husband then clubbed the stranger and put him in the oven. When he was cooked he was taken to the sharks to be eaten not at the pool, but away near Hoflua and Hatana islands. Hence people are never taken or eaten by sharks on the south (or Fakpui) side of the island. 5. BELIEFS AND SUPERSTITIONS. (1) OROI. Beneath the sea at various points opposite the six ancient states, but not the seventh and more modern division of Itumutu, lie regions where exist spirits—atua—who steal the souls, or lives, of human beings and feast on their bodies. The word atua, and its synonym, aitu, have been adopted by the christian missions to signify God: no benevolent god to the primitive mind, but one to be feared and propitiated. Mr. Churchward translates, in the Methodist version, the word aitu as God, god or spirit. Atua, he states, means a dead person or a ghost. By the Catholic mission Atua is used for God, as in Samoa and Tonga, but they here translate aitu as a malignant spirit, or devil. The Oroians seem to depend largely on human flesh for food. There are seven Oroi regions, all submarine. They are the abodes of the spirits of the dead, who are there re-embodied and become atua (see map). Hungry, atua return to the land by night to waylay roaming friends of their lifetime, and steal their souls. A portion of the atuan—a manifestation—enters the body of the victim. This of called suru-atua (the entry of a spirit) while the soul of the victim is taken to Oroi by the atua. Animated by its false spirit the bereft man continues his daily avocations, but his character has altered and resembles that of the soul-stealer when he, himself, was a villager. Then sooner or later the victim wastes away and dies. The Oroian is waiting for him to convey him to Oroi, where he in divided up and devoured. After this he, too, becomes an atua, and returns to entrap the souls of other men. "In any village, after a death," Marofu, the late chief of Noatau, told me, "if a certain smell comes in with the tide the people say, 'He is now being cut up for eating,' and children run, in terror, to their homes." The same chief related to me how, on the death of any Rotuman, an atua receives his re-embodied spirit and conveys it to Oroi. The route to the Oroi regions from, at any rate, the eastern portions of Rotuma, runs (like, I think, most spirit paths of the Pacific islands) westward, through Itumotu state to Losa. At a spot called Halasa the body or spirit (there is some obscurity here) is bumped against a rock. Thence, by places known as Lulu, and Chopunga, where they plunge into the sea, they proceed to the Oroi which is their destination The following is Mr. Gibson's translation of the legend of Tonuava, the man who visited Oroi: "At. the island of Selkope, south of Pepsei district, an atua from Oroi named Matavao used to visit the beach in the evenings at the time when the young folk were playing on the sands. One evening Tonuava of Pepsei approached him and invited him to his house for a meal. Matavao accepted the invitation. Tonuava noticed that Matavao only took one mouthful of each kind of food. During their conversation Tonuava expressed a desire to see Oroi. Matavao then invited him to his home at Oroi, warning him that he would see strange things and that Rotuma's daylight was Oroi's night. They agreed on a certain night when Matavao would escort his guest to Oroi. "On the appointed evening Matavao arrived during the customary play hours. After play they had food, and then set out from Pepsei. Toward dawn they reached Samoa village, near Motusa, and, as day broke, the village of Ruahau. Opposite this is a reef to which they walked on the water, without sinking, Tonuava following Matavao's instructions to step only where the latter stepped. From the reef they plunged down into the sea, Tonuava clinging to Matavao's wrist, and warned to be silent on their arrival at Oroi. "In time they arrived there. The injunction as to silence was unnecessary, for Tonuava could not speak, holding his breath while the hair on his head bristled like that of a wild boar worried by dogs. "They reached a public oval, facing the centre of which was the king's house, and on either side those of the most important people. Into one of these Matavao took Tonuava, who noticed that the hanging shelves were filled with food. Matavao explained that this had accumulated while he was absent, his share being brought regularly, whether he were there or not. "They talked well into the night, when Matavao took his guest to a sleeping place high up which had windows commanding a wide view of the place. In the morning Tonuava was told to remain there, out of sight, and to let no one see him. Shortly after this a great uproar was heard from an approaching crowd. Tonuava could hear them shouting the names of many people whom he knew in Rotuma. Another group appeared, and yet another, the last shouting the name Ngarengas and others of his tribe including Rafai of Juju, a personal friend of his own. "On asking Matavao for an explanation, Tonuava was told that while it was night in Rotuma spirits from Oroi went to hunt for wandering men into whose bodies they might enter. This done they returned to Oroi where the selected men would soon follow them. That it would not before Rafai and the others died, their souls having already been brought to Oroi. "There was silence after this, and, looking out Tonuava saw that it was night time. He noticed that the difference between night and day was less marked than at Rotuma. The night at Oroi was not pitch dark, but just gloomy, and the days not much brighter. "Tonuava, after this, returned to his home, taking with him a hanging shelf, a new kind of sugarcane—atuanasu—and a cock and hen." The cock and hen part is probably a modern addition. Mr. Gibson has supplied explanatory comments on the tale. He says that there are seven Oroi regions off the coasts. These are Vasere, south of Motusa, toward Fanguta; Limarae, opposite Losa; Fotiangpeu'u, opposite Ahau; Pukoru, opposite Malahaha; Houa at Oinafa, toward Fanguta; and Faliga-ono, at Fanguta. The spirit of a person is caught by the spirits of Oroi, and taken there. Once caught there is no escape, and sooner or later the person dies, and, in his turn, he becomes a trapper of human spirits. The following is a resume of Mr. Gibson's remarks on Rotuman superstitions generally. The Rotumans believed—and a large majority still believe—in ghosts and spirits. If one goes outside the house during the night and experiences a creepy sensation, or if an owl flies past, it is put down to the presence of the spirit of one newly dead. The relations of such, hearing of its restlessness, go to the grave to address the departed one or upbraid him, and this usually has the desired effect. An unusual roar of surf on the reef at certain spots by night, the crying of kalae (a bird), howling of dogs, or the sound of chopping wood, by night, are harbingers of death. If a man is wronged by another the evildoer is liable to a painful and lingering death by illness, unless he confesses, in which case he is cured. The sneezing of an apparently dying man is looked on as an omen of recovery; of the spirit returning to the body. At the first sneeze all in the room cry "sefua"! At the second they cry "ora"!, at the third "mauri"! or "life"! Any person disobeying or opposing a superior in rank is invariably punished by serious illness. There were, and still are, people who practise toak aitu or commune with spirits, and fortell deaths. The spirits of chiefs and prominent persons have entered rocks, stars, and planets, which were then called tupua. Living persons also have become tupua. (See the story of Moeatikitiki and his brothers.) Formerly male children were often dedicated at birth to Tangaroa showing him to be a superior aitu. (This last superstition probably came from Samoa.) Some other beliefs given by Mr. Gibson seem common to all races, ancient and even modern, and so are here omitted. 6. SONGS AND DANCES. The following is based on Mr. Gibson's notes and descriptions, and the verse and translations are furnished by him. At the present time—says Mr. Gibson-songs from Samoa, Tonga, New Zealand, Fiji and other parts of the Pacific are sung, but the old Rotuman songs and dances are also used. He gives the names of some of the modes or movements, as follows:— The Temo. This is sung, sitting, slowly and softly, with occasional light clapping and with a chorus of quicker time with clapping and a castanet-like finger snapping. It was formerly only sung for the supreme sau of Rotuma. The Hai-ne-maka. This is sung by men and women seated, with slow arm and body movements. At times a few performers rise and carry on the movement standing. It should be sung for chiefs only. The Ri-joujou (tchoutchou). A lively dance and chorus for both sexes. The Mak-paki. A men's club-dance. The Kau. A men's war-dance. The Kautonga, an importation from Tonga. Notes by compiler. Dances are accompanied by a vocal orchestra, with occasional clapping, and bamboo striking. The orchestra sits apart. In their chants there are few intervals. Speaking, now, from memory, I seem to recollect, in any one chant, but two tones, in, roughly, thirds or fourths. It is the primitive music described by Mr. Johannes C. Andersen-reprint vol. 10, Poly. Soc. . Journal—and Mr. E. G. Burrows, in the same Journal, no. 195. For mission purposes the modern scale has been introduced and is now familiar to the people. In the following examples the first has four-lined stanzas, rhyming in the last foot of each line, while, in the second, each verse is in crudely rhyming couplets. In the first line of each stanza I have placed a long accent mark over the accented vowels to indicate the general metre. [not present in electronic version; A.H.] In examples and translations I use phonetic spelling for personal and place-names and for words containing, in Mr. Gibson's writings, the letters g and j. The former is pronounced ng, the latter tch. EXAMPLE 1.

Notes by Mr. Gibson. (a) The first sau or king of Rotuma. EXAMPLE 2.

(a) "Eye of men" or "foremost." 7. VOYAGES OVERSEA. Canoe voyages were made by Rotumans, according to Mr. Gibson's informants, to Tikopia, Malekula, Santo, Nanumea (Ellice Is.), Tonga and Fiji. One Pani, and two others of Malahaha and Losa, are said to be the last of such voyagers to go and return. From Uvea (Wallis Is.), Futuna (Home Is.), Tonga, Fiji, Tamana and Tarawa (Gilbert Is.) There is an old Gilberteese burial place in Rotuma, and also Tongan and other foreigners' graves. There was at least one raid by cannibals, as mentioned in my history section, and captured invaders were seen by early European voyagers. 8. SOCIAL LIFE, PAST AND PRESENT. The Rotuman states or kingdams were composed, like the present districts, of village communities. Each state was ruled by a pure ngangatch, who controlled its politics of peace and war. Although a dictator, public opinion, and a possible resort to revolution obliged him to keep within the customary law and rule with discretion. His office was elective within the hereditarly leading clan of the state. In the case of the Noatau state—now a district—its ruler, on installation, took the titular name of Marof, and the phrase for installing is translatable as "to Marof," The name in full is Marofu but the shorter form is more honorific. The district of Noatau is and was pre-eminently the leading district. Mr. Gibson considers the name Marofu to have been derived from the Tongan chiefly name of Maafu. In my historical section I have shown-supported by the traditions of the Samoan invasion—that the invading leader, Raho, was apparently of mixed Samoan and Tongan blood, but there was, also a later Tongan invasion. The custom of a titular name for the successive state rulers was not observed in the other six states of Rotuma. The state ruler did not interfere in the interior affairs of the clans where they did not affect the state in general. That was the duty of the pure of the kauanga or clan. The ruling pure had certain officials in his itu or state to assist him as pure nganatch ne itu. There was the mafua, his official herald, speaker, and master of ceremonies; a tonu, his ambassador and representative. His general was called a toke and in battle he had a faufesi who was personally responsible for his life, and disgraced for ever should he survive the death of his chief in combat. This official had the privilege of being served with kava before his king. The haharangi were the young warriors. The villages of the state were usually divided—as they still are—into wards, each occupied by a clan, with lesser family or household divisions. To each village there was a mayor, pure ne kauang hanua. Chiefs of wards were pure ne hoanga, and there were also pure ne kauanga or chiefs of clans. These dignitaries constituted a village council. They were consulted on state emergencies by the pure ngangatch (ruler), who seems to have treated them as executive officers. The system to a great extent remains, and is utilized in modern administration. The days of war have vanished and been forgotten, and the discordance between adherents of the Roman-catholic and Methodist missions are hushed. Village life proceeds peacefully and happily. The men build, fish, and cultivate their food plantation. The women keep more strictly to domestic duties than elsewhere in the Pacific. There is not the picture of the proud man stalking ahead while the women bear the burdens, so common in Melanesia and much of Polynesia. The greatest consideration is shown for the aged of both sexes. The children are idolized and spoilt. The Rotumans are a contented and merry people, not unindustrious, but full of the joie de vivre. They have many sports and pastimes. Picnics are quite a feature of their lives, while dancing, singing, wrestling, and various local games, from tinga (a kind of lance throwing) to cat's cradle. The merry old women enjoy life with the young. They are privileged in many ways, both as advisers and jesters. They may drag a high chief violently from his seat into a dance, and even the resident commissioner has been subjected to this, with loss of dignity to none. They are zealous churchgoers nowadays. Dissenting creeds, rife in many groups of the Pacific, have not crept in. The chiefs and people have much local and tribal pride. In the council of chiefs, over which the commissioner presides, the order of precedence is strictly observed and the same occurs at all feasts and ceremonials. At the beginning of a round-island road scheme the chief of Noatau was much upset because the work did not commence in his —the premier—district, notwithstanding the fact that his section of road was on hard sand, not, at the time, requiring repair. Again, on the allocation in the council of chiefs of the shares of annual taxation payable by each district, in example of district pride occurred. In 1880 the first assessment of taxes to be levied from each of the districts of Rotuma was in proportion to the copra being then sold to traders in the different states. It had no relation to populations. The same basis had been used ever since, the only difference being in the total assessments for the whole island, subject to subassessment per district, the proportions remaining at the same ratio. Districts with small populations were, in some instances, contributing consider-ably more than others with larger populations. On sounding the chiefs as to their feelings on this anomaly, which operated now quite irrespective of production, I found that district pride refused to consider the reduction of its contributions to an amount lower than its perhaps more wealthy and populous neighbour. And so we left it.

Frederick Gibson (1886-1945) |